Cross-posted from Media Mythbusters

Into The Fray – The Cowles Dynasty and the Media

Oct 30th, 2007 by Terresa Monroe-Hamilton

Cross-posted at NoisyRoom.net:

Currently, I am looking into pulling together a timeline for media incidents concerning the Cowles’ Family Dynasty in Washington state. Larry Shook of Camas Magazine is the go-to source on this subject. As he points out, the Cowles have ruled the Spokane area with an iron financial fist for better than a century and along with marking their territory, they allegedly control the media. Below, you will find an excerpt from Larry Shook’s upcoming book, ‘The Girl From Hotsprings.’ Who says local politics are boring? You’ve got all the ingredients for a great story here: an all-powerful family, disappearing informants, money changing hands and one guy who is out to tell the truth no matter the cost. Ladies and gentlemen, I give you Larry Shook – let the games begin:

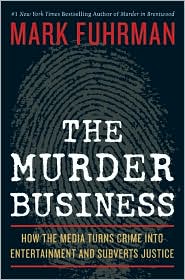

Excerpted from The excerpt below is taken from the first chapter of my forthcoming book, The Girl From Hotsprings, which will be published in 2008, Copyright Larry Shook. I read a portion of the material below on the Mark Fuhrman radio show on Friday, 10/26/07.

The Girl From Hotsprings,

Copyright 2008 by Larry ShookThe context of this excerpt is that in December 2003 I was trying to get in touch with former Spokane, Washington City Councilman Chris Anderson. The evidence suggests that Mr. Anderson was run out of town by the powerful Cowles family, a media dynasty that has controlled Spokane’s media for more than a century. (See “Newspaper Monopoly Town,” www.girlfromhotsprings.com.) For an account of Mr. Anderson’s disappearance, see “Missing Man” at www.camasmagazine.com. Mr. Anderson’s sin appears to have been his opposition to the massive public subsidy of the Cowles family’s River Park Square shopping mall. I had been told that a man named Mike Matheson was Anderson’s best friend; if anyone could persuade Anderson to talk to me it would be Matheson. But as soon as I told Matheson the reason for my visit to his house, he grew agitated. I feared he was about to evict me. The story picks up there.

At the mention of River Park Square, Matheson relaxed. He said he had heard of our work. At that point, a lot of people had.

“As you know, Chris Anderson was the only city councilman who opposed River Park Square,” I said. “All the public knows about him is what the newspaper reported.”

Matheson and I kicked around the subject of River Park Square: How the controversy surrounding it had engulfed Spokane for years, even making national headlines—The Wall Street Journal ran a front page story about it; Time and Forbes magazines blasted it as “corporate welfare.” How the Cowles family, The Family, the mall’s owner, had used its newspaper to front for the development (“Cowles Clan’s Many Interests,” read one of the Journal’s heads); how, as Matheson and I both understood, The Family also used its newspaper to drive Chris Anderson from town.

“I wish I could help you, but I can’t,” said Matheson.

Reporters learn to take such answers with a grain of salt. You want to gently give sources a chance to think things over. Many people, you learn, do have this still small voice inside them that they listen to. And every now and then—often enough to make patience worthwhile—that little voice changes their minds about helping reporters. Most people, in my experience, are willing to aid and abet the truth—so long as they can duck its backscatter. I don’t mean that as cynically as it sounds. The world is imperfect, impure. It can take people hostage. Spokane, in its own special way, was the most impure place I had ever seen. I wasn’t alone in thinking that the River Park Square scandal revealed the extent to which the Cowles family holds Spokane hostage. An entire American city held hostage by its newspaper, of all things.

Still, Chris Anderson obviously had a powerful conscience. And he was clearly a fighter. And Mike Matheson didn’t strike me as a shrinking violet.

“Did Chris ever talk to you about River Park Square?” I asked him.

He studied me for a moment, then nodded his head.

“Chris comes to me and he says, ‘Mike, I’ve opened a can of worms, and it’s really bad.’”

Right. I knew that. In fact, I probably knew things about the can of worms Anderson had kicked over that Anderson himself didn’t know.

This was because of all of the reporting we had done. We had many hours of tape-recorded interviews with people who would go on the record. We probably had as many or more hours of off-the-record interviews. The latter gave us a glimpse of the submerged part of the massive iceberg known as River Park Square that Spokane’s ship of state had been steamed into. That’s right; it was deliberate. Spokane’s public officials had steered their constituents right into that iceberg, and now the passengers of Spokane were expected to save themselves by putting up as much of their municipal funds as necessary to bail themselves out. Literally. In the secret insidious details of River Park Square was the proviso that the city would lay off policemen, firemen, raid the park budget, close libraries if necessary, all to pay for the expansion of the Cowles shopping mall.

And then there were all the documents we had acquired. Sheaves and reams of them, documents by the cord, it seemed. Documents that were never supposed to see the light of day.

Like the “divide and conquer” memo River Park Square developer Betsy Cowles had written on March 9, 1995. That memo had become an exhibit in the federal securities fraud trial that our reporting helped trigger. I say that, because our reporting was cited as evidence in the complaint filed by four of the nation’s leading financial institutions.

In this particular memo, written to her project manager (a man named Bob Robideaux), Cowles laid out a strategy strongly suggesting that she intended to commit several kinds of fraud. She planned to leverage some $100 million in public funds to redevelop her family’s shopping mall, and the paper trail showed that she didn’t mind coloring outside the lines to get the money.

Betsy Cowles is a lawyer, and the evidence suggests that she knew full well, or should have known, that she would be defrauding bond purchasers, the U.S. Treasury, and the taxpayers of Spokane. For non-newspaper owners this would typically be a delicate situation. Provable intent to violate law in such circumstances is one thing that can trigger a criminal indictment quicker than you can say federal grand jury. And in most parts of the country, an elected official trying to stop criminal fraud would be a hero. Cowles’s memo to Robideaux, however, suggests that the recalcitrant Councilman Anderson was no hero to her.

“The only way we are going to get all of this done,” Cowles wrote Robideaux, “is to divide and conquer as much as possible.”

Her target for division and conquest: none other than the elected government of Spokane, Washington, second-largest city in the state.

Cowles picked out one councilman, a realtor, for an early “informational meeting,” but whatever information she wanted to share with that councilman she didn’t want spread around. “I think I want to hold off on meeting with the other council members at this point,” she wrote “because I don’t think we are ready for too much information to leak too quickly. But I do think they should be on our hit list. When the time is right and depending on our message, for efficiency sake we might divide up the list. You take half and I take half (we can draw straws as to who gets to talk to Chris A.!).”

A hit list? Talk to Chris A? About what? It’s interesting to speculate what an aggressive federal prosecutor—a Ken Starr, say, or a Patrick Fitzgerald—would do with questions like that.

A cornerstone of Cowles’s River Park Square financial strategy called for the sale of $31.45 million of bonds backed by the municipality of Spokane. The bond proceeds would go to Cowles real estate companies. The problem with Cowles’s concern about too much information about her project “leaking” out is that it flew in the face of federal securities law. Federal securities law requires full disclosure of all known material facts about risks associated with purchasing securities. Get cute in withholding information like that and you could get slapped with a securities fraud suit quicker than you can say Securities Exchange Commission.

Elsewhere in the divide and conquer memo, Cowles touched on other important secrets of her deal suggestive of an organized criminal conspiracy involving her family’s various companies and various public officials. Among the secrets: the way a downtown street had been vacated that the city would lease back from the Cowleses at an exorbitant rate; the details of how more than $45 million of city parking meter revenues would be used to secure the bonds; the hidden subsidy of a $23 million federal loan to build a new Nordstrom department store; the secret refusal of the Cowles family to honor federal guidelines and put up collateral for that loan.

While this single memo was a drop in the bucket of evidence that Cowles had engineered a stunning fraud, it did go to the heart of what the IRS would later call a “scheme.” A scheme that used “smoke and mirrors…. to hide the true nature of the transaction.” A scheme concocted by a developer (that would be Ms. Cowles) who “had, and continues to have, a particular relationship with the City of Spokane… such that it was in a position to control or influence its activities.” A scheme in which “the casino was rigged… in order to unjustly enrich and profit the developer.”

But it didn’t matter. Cowles, the City of Spokane, and virtually everyone else associated with River Park Square were sued for securities fraud in the spring of 2001. The IRS, also citing our reporting, was investigating whether the RPS bonds violated federal tax code.

When investors in the Cowles garage sued, and the IRS launched its investigation, the drama surrounding the Cowles mall changed. Fraud is a loaded word. In the everyday sense it means deception. In the legal sense it means someone’s legally protected rights were violated in a way for which there is a legal remedy. A legal remedy is a socially codified mechanism for restoring victim losses and giving perpetrators consequences meant to dissuade or prevent future perpetration. Convicted perps—Martha Stewart, Andy Fastow, Ken Lay—are paraded before the media in a ceremonial perp walk, their hands conspicuously cuffed. Their public humiliation is meant to reinforce what Piaget called “externalized morality.” This is the same reason cops give us speeding tickets. It’s an object lesson: no one is above the law. And yet no one was talking to Chris Anderson, perhaps the only eyewitness who might talk about what critics would call the “heist” that city officials had helped the Cowles family bring off in broad daylight.

By the time I rang Mike Matheson’s doorbell I had a mountain of documentation suggesting that Betsy Cowles had, at the very least, perpetrated the kind of fraud that represents intentional deception. But it’s socially unacceptable to say that sort of thing in Spokane because of her wealth and power.

Betsy Cowles is a daughter of American publishing royalty. Her father, grandfather and great grandfather had been directors of Associated Press, the most powerful news organization in history. And they commanded a media empire that gave them virtual suzerainty over a sizeable chunk of the American west. And her widowed mother re-married to the great Punch Sulzberger, former publisher of The New York Times, the nation’s newspaper of record, perhaps the most influential single publication in history. (Arthur Ochs “Punch” Sulzberger, of course, was also the man who risked jail to bring the world the secrets of the Vietnam War contained in The Pentagon Papers.) But neither he nor anyone else at The New York Times was lifting a finger to expose the secrets of what his new wife’s family had done in their remote barony. Because of her connections, Betsy Cowles would never be held to account for what she did in Spokane, said the town’s smart money. Not even for a woman’s death in which Betsy’s actions, those of her uncle Jim, and those of certain city officials would eventually implicate them all. That’s what the smart money said. That’s what the smart money had told me again and again. So far the smart money had been right.

And that is the subtext of the story that made me yearn to talk to Chris Anderson.

It looked to me as though Anderson had fought a brave and lonely fight. I have a warm place in my heart for people like that. The world takes people hostage, yes. But not everyone. Some people learn to free themselves, and they set a powerful example, and I wondered if Chris Anderson was one of these. It also seemed that Chris Anderson had been an eyewitness to an astonishing financial crime that wound up, as a famous retired sheriff would eventually charge, being a crime against a person, too.

A reporter’s business is documentation. I already had enough documentation to have helped launch a securities fraud suit and an IRS investigation. But there is no documentation like the tape-recorded account of an eyewitness. I desperately needed an eyewitness.

Let me be clear about something here. The story I am about to tell you is complicated. It’s also important. It’s also flat-out fascinating as an exhibit of human nature and the vulnerability of democracy in America (and everywhere else, for that matter) to corrupt media.

In Spokane, the corruption had taken the form of a kind of simony. Simony, recall, is the sale of ecclesiastical pardons. According to the New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia, “Simony is usually defined as ‘a deliberate intention of buying or selling for a temporal price such things as are spiritual… While this definition only speaks of purchase and sale, any exchange of spiritual for temporal things is simoniacal… The various temporal advantages which may be offered for a spiritual favour are… usually divided in three classes. These are: (1) the munus a manu (material advantage), which comprises money, all movable and immovable property, and all rights appreciable in pecuniary value; (2) the munus a lingua (oral advantage) which includes oral commendation, public expressions of approval, moral support in high places; (3) the munus ab obsequio (homage) which consists in subserviency, the rendering of undue services, etc.”

By the time I called on Mike Matheson, I had overwhelming evidence, much of it already published by my colleagues and me, that Betsy Cowles’s River Park Square mall was a textbook example of media simony. Those who facilitated her deception, including a man who would become the U.S. attorney for Eastern Washington, were rewarded with favorable press in her family’s newspaper. Those who opposed it, including an elected mayor, were subjected to vicious editorial attack. Ironically, the simony that helped drive the Cowles mall even corrupted a prestigious Catholic university.

If I ever confuse you or bore you or cause you to distrust me by not documenting the outrageous things I’m about to tell you, then I have failed. It means I wasn’t equal to my task. But if this story makes sense to you and you ever once feel like a mere armchair observer, then you, gentle reader, are the one who has failed.

So when I say I needed an eyewitness I mean you needed an eyewitness. Because, under the law, I work for you. The First Amendment—by my lights the grandest canon ever sprung from the suffering breast of humanity—is about much more than looking for semen stains on ladies’ dresses.

The other day a radio talk show host asked me, tongue in cheek, I suppose, if I ever felt like I was in the middle of a Robert Ludlum novel. The question surprised me; I chuckled and said the thought had crossed my mind. But that wasn’t true. Ludlum wrote fairy tales. Never once from the moment I started reporting on Betsy Cowles’s shopping mall did I feel like I was in the middle of a fairy tale.

If what I have written so far and what I am about to write is not true—if I have made up or adulterated documentation for my reporting for the malicious purpose of harming people—then I have a problem. It’s called libel. In this case it will be a very big problem. Because it will mean that I have libeled some very wealthy, very prominent, very powerful, very litigious people.

If I write the truth, on the other hand, my problem is different. It will mean that there is an American family, and an American city, that is beyond the law because of the ensorcellment power of The Family’s media. And that is a problem we all share. If you think not, if you think Spokane’s problem doesn’t affect you, I suggest you keep thinking. Keep thinking until you come to this question: how likely is it that Spokane and the Cowles family are unique in the human experience?

The book continues from there. Other excerpts can be read at www.girlfromhotsprings.com.

Not quite done here for today folks. Following is a very interesting exchange that I was forwarded this morning from Rocket’s Brain Trust. It is from Larry Shook concerning events with the Cowles’ Dynasty and the money trail left behind. This definitely caught my eye this morning and will be worked into the timeline. I believe this is for the Mark Fuhrman show. RPS stands for ‘River Park Square.’

Subject: Follow the money

Rebecca:

If you and Mark–or your listeners–are interested in being informed monitors of the never ending soap opera-like RPS drama, you might want to watch the sub-plots unfolding around a couple of issues.

The first issue has to do with my public charge that RPS evidence suggests that the Cowles family uses its media, particularly its daily newspaper, as an instrument of fraud in an on-going criminal enterprise to misappropriate public money for its own business interests. As I told you when I first appeared on your show last August, because I’m wrapping up more than seven years of research in completing my book on the RPS episode, I’m prepared to speak plainly, when asked, about my conclusions. In the book itself I’ll speak as plainly as I know how.

The second issue concerns the so-called “audit” of Spokesman-Review coverage of RPS done by the Washington News Council. As Tim Connor’s audit of that audit points out, the News Council’s work, instead of answering all the important questions, posed significant new ones. As Tim reported, the News Council simply made up important facts that go to the heart of the RPS scandal. One concerns the huge law firm, Preston Gates and Ellis. (And, yes, the Gates in this firm is Bill Gates, Sr., father of the world’s richest man.) (And, yes, Preston Gates and Ellis is the same blueblood Seattle law firm that got entangled in the Jack Abramoff scandal.) After Betsy Cowles, Preston Gates and Ellis (particularly Spokane attorney Mike Ormsby and Eastern Washington U.S Attorney Jim McDevitt) would probably be considered the top suspects in the RPS securities fraud case. This was because the firm represented the seller of the RPS bonds in ways that entailed several alleged commissions of federal securities fraud. (The seller of the RPS bonds was the Spokane Downtown Foundation. Both bond purchasers and the IRS cited evidence that this supposedly independent non-profit organization was itself nothing but a fraud, a storefront created by the Cowles family for no other purpose than to peddle the RPS bonds. See “Fraudville, USA,” and “The Casino Was Rigged” at www.camasmagazine.com) In purchasing the bondholders’ lawsuit—a suit that alleged the fraud that constitutes the heart of darkness in the RPS deal—the City of Spokane essentially admitted the fraud and confessed to its role in it. Again, misters Ormsby and McDevitt were key players in Preston’s RPS activities.Spokesman-Review editor Steve Smith promised to lay to rest charges that his paper effectively suborned fraud with its RPS coverage by commissioning an “independent audit.” His auditor: the Washington News Council. One of the News Council’s key members: Preston Gates and Ellis. Another of its key members, the international PR giant, Hill and Knowlton, the firm the Cowles family turns to for public relations counsel from Rockey Hill and Knowlton. The facts made up in the Smith/News Council audit: 1) The IRS “reversed” itself and ruled that the RPS bonds that funneled millions of dollars of excess profits into Cowles real estate companies didn’t violate IRS code after all. 2) The IRS left the tax-exempt status of the bonds intact. 3) Cowles double-duty real estate/First Amendment attorney Duane Swinton didn’t have a conflict of interest. Those three assertions are wrong, concocted out of whole cloth, and illustrate the highly contagious nature of the RPS fraud. (See “All In The Family,” www.camasmagazine.com.)

The facts are, 1) the IRS didn’t reverse itself, according to the IRS itself; 2) not only were the bonds ruled taxable, Preston Gates and Ellis itself paid the taxes, effectively under the table in an arrangement that makes the sum a secret–yes, one more secret added to the RPS “Official Secrets” folder; and 3) the Washington State Bar Association finds evidence of Swinton’s conflict of interest so compelling that it has agreed to investigate it as a result of a bar complaint filed by Tim Connor.

I believe the RPS perps are playing the public–and this includes law enforcement and government regulators at all levels–for suckers who are too dumb to understand the RPS shell game, and too scared of the Cowles family to take them on over it. Like all shell games, this one is complicated only until you understand how it’s done. Tim Connor’s report on the News Council audit (see “The Verdict” at www.camasmagazine.com) helps expose what looks like a new level of cover-up in the RPS “scheme.” Scheme was the IRS’s word.

All of this raises a new follow-the-money opportunity for citizen observers and government investigators. Was Preston Gates and Ellis money laundered into the Washington News Council to fund its dubious audit of the Cowles newspaper? And is Preston money being laundered into the campaign of Spokane Mayor Dennis Hession right now in the form of the $10,000 loan from Preston lawyer, and erstwhile RPS fraud defendant Ormsby, as a way of saying, “Thank you, Your Honor, for keeping the RPS fraud good and buried”? Is this loan a reminder to the mayor to, “Remember the slogan, Your Honor–we have to put River Park Square behind us”?

At the very least, as retired economic crimes detective Ron Wright points out, these are important questions for criminal investigators from the U.S. Department of Justice to explore. Of course, Spokane Police Chief Anne Kirkpatrick could ask the Criminal Investigation Division of the Washington State Patrol to launch such a probe right now, but that’s another matter.

By helping your listeners understand and follow these sub-plots you can continue to shine a light into the RPS mineshaft. Thanks for your interest and efforts.Sincerely, Larry Shook